As the seasons change, herds come and go on the slopes of the Alps. Inalpe and désalpe are celebrated by men in the heart of the valleys. What is this age-old tradition that enchants the alpine pastures and resonates beyond the highest mountains? Let's set off together to discover transhumance in the Alps.

Transhumance in the Alps: The birth of an age-old tradition

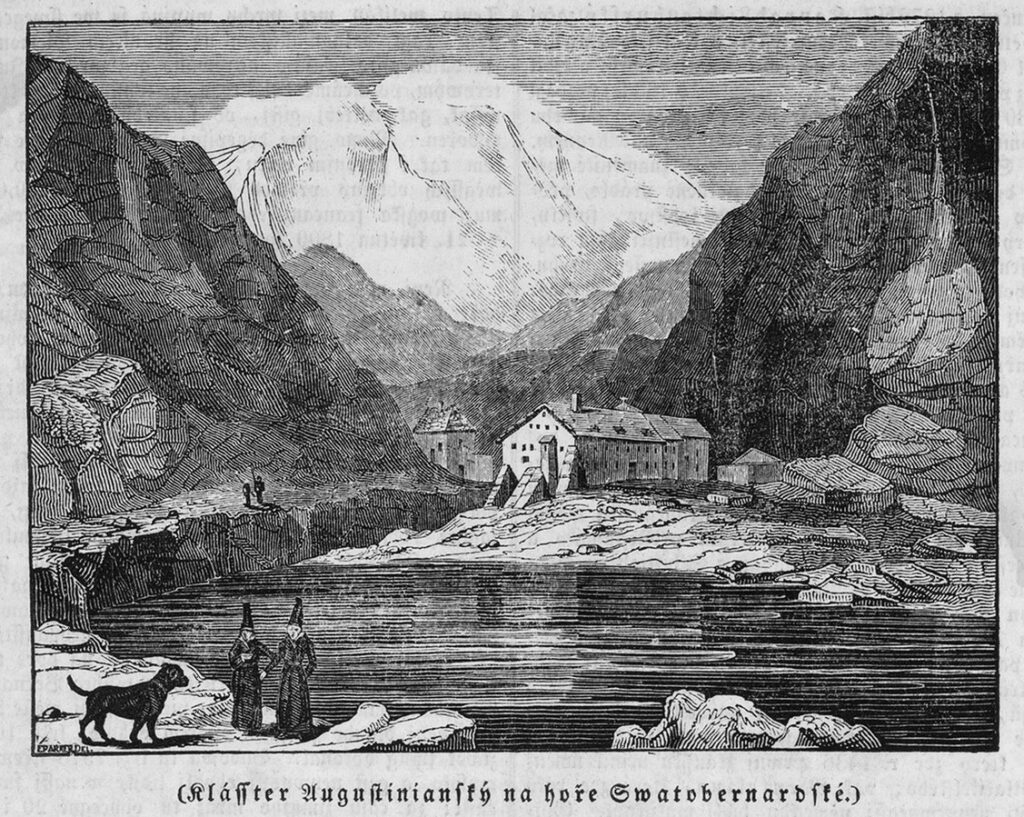

In the heyday of the Middle Ages, people made their environment their own. They spread their livestock across the high pastures according to the seasons. Between the Alps and the Mediterranean coast, herd movements became more widespread. This was the birthplace of transhumance, Latin for "beyond the land". Since the 12th century, the Alps have lived to the rhythm of the incessant comings and goings of sheep and cows, which spend the summer at altitude and return to the plains in autumn to find refuge. The fatty grass of the meadows, protected from the animals' appetites, becomes invaluable winter fodder.

Transhumance is seasonal when, each year, shepherds lead their flocks to the same meadows. These mountain pastures are home to cattle and sheep all summer long. In the Alps, this migration to the mountain pastures is known as inalpe, while desalpe refers to the return of the cattle to the stables at the start of winter.

Winter transhumance is when farmers lead their sheep from one meadow to another during the cold season. If they don't have enough fodder to fatten their animals in the sheepfold, they offer them the fresh air and starry nights. In the Swiss Alps, these flocks congregate under the shelter of the snow, on the ever-green expanses that farmers make available to them. Sheep graze and enrich the soil with manure.

As the daughter of pastoralism, transhumance helps to sustain the local economy and promote quality alpine products. But above all, this ancestral custom contributes to the preservation of the mountain ecosystem and heritage. Summer grazing has created such a precious mosaic of forests and pastures in the highlands that safeguarding this alpine landscape is even enshrined in the Swiss Constitution.

Transhumance in the Swiss Alps: When inalpe becomes poya

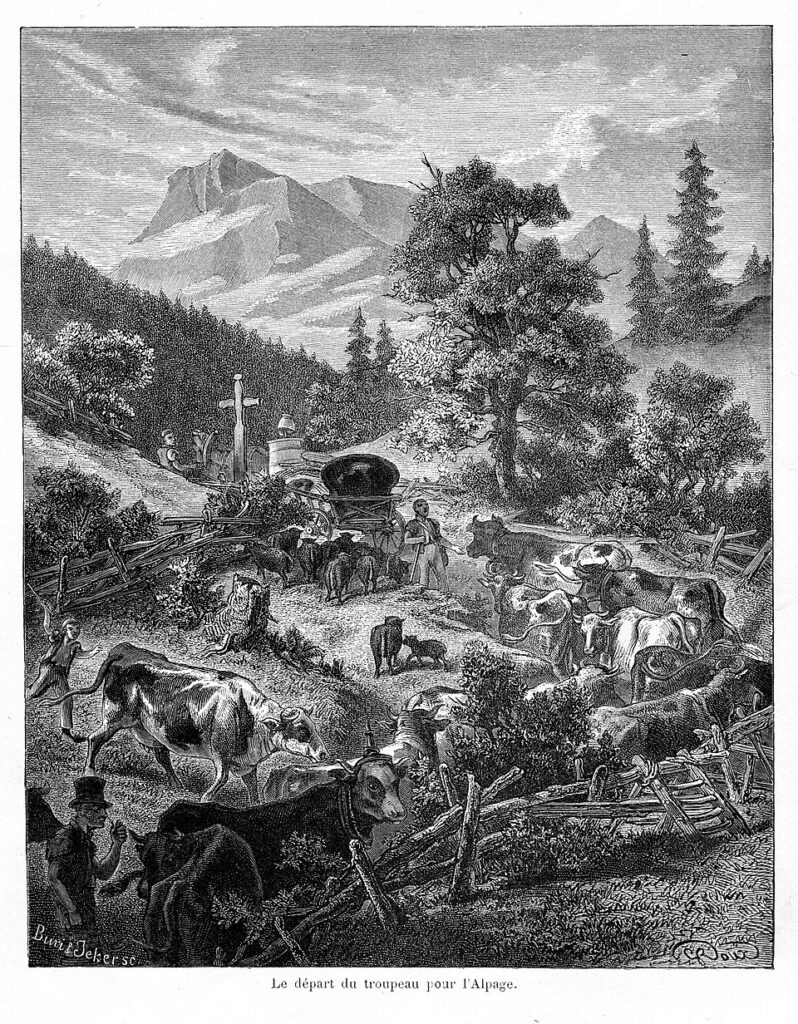

In the Swiss Alps, transhumance takes on a different guise. The inalpe becomes the poya, as in the Aosta and Chamonix valleys. As the snow fades and life returns to the high pastures, the summer winds sweep across the plains. The event is approaching: a Saturday in late May or early June. So, we get up at dawn, the herds are restless. They know it's time to head for higher ground. Time to feed on fresh pasture and finally enjoy the softness of the sky.

Each canton has its own speciality. At the Valais inalpe, the most robust cows engage in queenly battles to assert their power over the herd. Whereas in the canton of Vaud, the hierarchy is established in relative calm. Up there, transhumance perpetuates Swiss traditions. What would the canton of Fribourg be without its alpine Gruyère cheese, produced since the 16th century? What would the Swiss mountains be like in summer if they didn't resound to the inimitable sound of cowbells?

Summertime is a time for popular festivities. Armaillis, the shepherds of the Swiss Alps, dress up in their finest costume. The bredzon consists of a jacket embroidered with edelweiss, pants, a shirt and a straw cap called a capet. They sling a saddlebag for salt over their shoulders and walk proudly with a cane in hand. It's a race to see who can lead the most beautiful animals. The cows are adorned with magnificent flowers, and some sport imposing bells that sing of fine weather and stir the heart. As part of the procession, a mule pulls a cart carrying all the equipment shepherds need to live well in the alpine pastures and make their best cheeses.

Desalpe or the return of summer in the Swiss Alps

When day gives way more quickly to night, and the grass begins to grow sparse, the herds leave the mountain pastures and descend into the valleys, led by their guides. The time has come for desalping or rindya in the Swiss mountains. Around their necks, the cows no longer wear their grazing bells, but a huge bell whose echoes echo across the paths to announce their return. Adorned with flowers, they know it's time to return to the barn.

The shepherds, also dressed for the occasion, start the transhumance at mid-day, reaching the villages in the afternoon. The lead cow leads the way, followed by the older animals, while the younger, more fearful cows follow the herd. As the herd makes its way up the mountain, villagers and tourists gather in the streets to welcome it. In a popular atmosphere where folklore mingles with joie de vivre, the crowd cheers the return of the animals. The cheese produced in the alpine pastures during the summer is given pride of place. In this way, the Alps celebrate the land that nurtures them through the seasons. Then, as night falls, drunk with music and delight, everyone returns home to celebrate the return of the shepherds and their flocks.

Transhumance in the Alps: the future of pastoralism

Transhumance, the seasonal movement of flocks and herds, is now part of humanity's intangible cultural heritage as defined by UNESCO. Whether practiced in France, Austria, Italy or Switzerland, transhumance enjoys a status worthy of its roots in Alpine culture.

Now internationally recognized, it is nevertheless threatened with extinction. Becoming a shepherd is a vocation, as the job is so tough and demanding. And the consequences of climate change on Alpine landscapes are not helping matters. Glaciers are retreating, snow is less abundant and water is scarcer at higher altitudes. How can we meet the needs of our herds and our people? How can we maintain our cheese dairies if there's not enough water in the mountain chalets? Mountain meadows are also becoming rarer, as previously unspoilt land is being built on or cultivated. The very way of life of modern farmers and the industrialization of agriculture do not encourage this nomadic lifestyle either.

Beyond the picturesque image that appeals to the public, how can shepherds perpetuate the long tradition of alpine transhumance? At a time when agroecology is gaining ground, the future of pastoralism lies in their hands. Thanks to their know-how, their perfect knowledge of the Alpine environment and their deep attachment to transhumance, they need to reinvent this way of life that has been rooted in the history of the Alps for centuries.