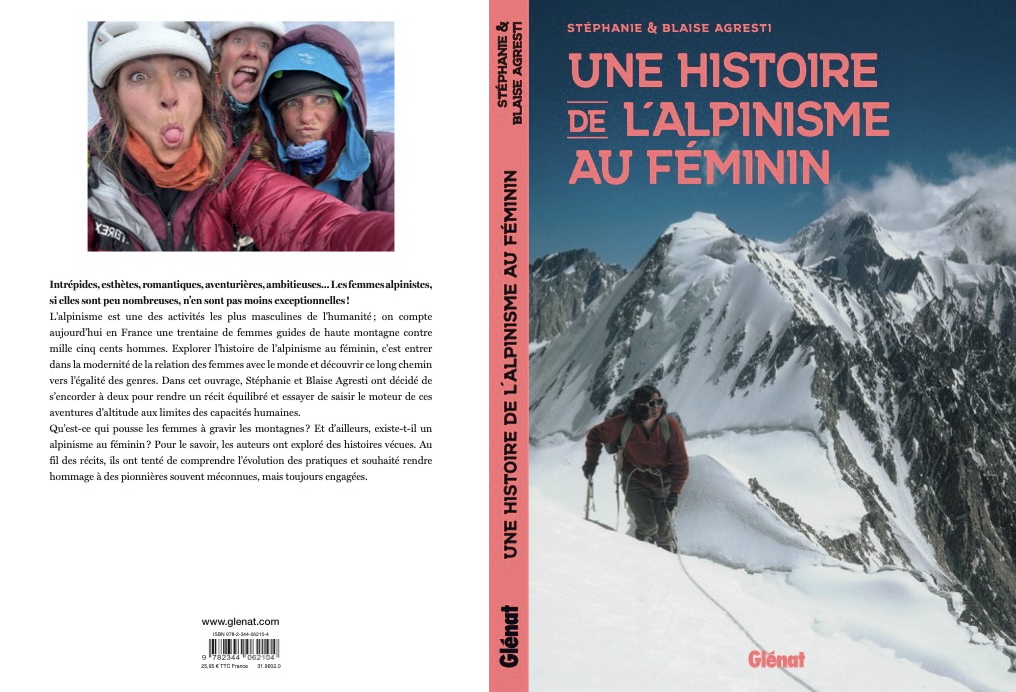

There are stories that time too easily forgets, tales of summits climbed and exploits buried in the shadow of giants. Blaise and Stéphanie Agresti have taken it to heart to restore the memory of women mountaineers in their book "Une histoire d'alpinisme au féminin", published in 2024 by Glénat. Together, they seek to repair an oversight in the history of mountaineering. After an initial exchange with Blaise Agresti about his career and his vision of the mountains, I invite you today to discover the continuation of our conversation. Today, the book's co-author offers us an inspiring reflection that leads us to rethink our own relationship with the mountains.

Women mountaineers: from social challenges to inspiring stories

What do you think have been the main difficulties women have faced throughout history in gaining access to mountaineering?

The obstacles women have encountered in mountaineering are no different from those they face in becoming a company CEO or President of the Republic. They are the same difficulties, mainly sociological. There's the traditional assignment to motherhood, the idea that women shouldn't take too many risks, that they should protect the home. It's a very deep-rooted anthropological interpretation, and one that wasn't confined to mountaineering.

Initially, no one really questioned whether it was right or wrong for women to take up mountaineering. Things just happened that way, naturally imposing these sociological barriers. But there is also a specific dimension to mountaineering, linked to the history of its creation in 1857 with the Alpine Club. It was an all-male club, made up of members of the English aristocracy, with its own rules. Women were obviously excluded from a cigar-smoking, whisky-drinking club. It wasn't until 1970 that women were finally allowed to join the Alpine Club. The activity itself was therefore originally created for men, just like other sports such as rugby and soccer.

Today's rebalancing is the result of a long cultural and sociological process. During our search for the book, we noted that certain historical moments had particularly contributed to the evolution of women's place. For example, during the First World War, men were at the front and women had to take charge of the economy, in France and elsewhere in Europe. After the war, in 1918, there was no turning back the clock once women had managed businesses and farms on their own in the absence of men. These historic events gradually redressed the balance of power.

However, there is also an anthropological reality linked to motherhood and risk-taking that cannot be ignored. Mountaineering is a high-risk activity. So we can't claim absolute fairness, because a mother, regardless of the outside view, simply can't have the same exposure to risk. All the women mountaineers whose testimonies we gathered confirmed this: their relationship with risk and high altitude changed after having children. There's clearly a before and an after.

These dimensions need to be recognized. To say that men and women are totally equal is not accurate: we have differences, distinct ways of apprehending the world. The idea is not to deny these differences, but to invite the female gaze to play a full part in the overall story of mountaineering.

Of all the women mountaineers you mention, which ones particularly inspire you? For which reasons?

There are two women whose stories have made a particular impression on me.

Lucy Walker was the first woman to climb the Matterhorn, in 1871. This was just six years after Whymper's famous first ascent in 1865, during which half the team lost their lives. Everyone knows this historic date - it's firmly anchored in the history of mountaineering. And yet, only six years later, Lucy Walker climbed the Matterhorn with a guide, dressed in a dress, using a hemp rope, with no helmet or special equipment. The climb went remarkably well, and they made rapid progress, but hardly anyone talked about it until very recently. Lucy Walker's story and her magnificent ascent of the Matterhorn really deserve to be better known.

My second favorite is Kate Richardson, an exceptional woman. Between 1880 and 1890, she achieved incredible feats in the mountains. She regularly achieved long days with 2,000 to 3,000 meters of positive vertical drop, in extraordinary weather, linking summits over 4,000 meters from valley bottoms. Among her achievements, she was the first person, men and women alike, to traverse the Bionnassay ridge in the Mont Blanc massif. At the time, this ascent was considered impassable. Setting off at midnight from the valley at an altitude of around 1,500 metres, she completed the traverse by ten in the morning, covering more than 2,500 metres of ascent with remarkable efficiency. She was also an excellent climber, having completed one of the first traverses of the Drus. Yet today, almost nobody knows her.

Kate Richardson was a woman of exemplary modesty. It is assumed that she was in a relationship with a woman. Out of love for this companion, who could no longer practice mountaineering because of health problems, Kate is said to have decided to give up the mountains. It's also a touching story about the complexity of love relationships, which were particularly difficult to come to terms with publicly at the time. Kate embodied a transgressive lifestyle model for her time, while demonstrating remarkable ethics, profound humility and a very high level of performance. Her story is extremely modern, and I urge readers to discover the chapter devoted to her in our book. They will meet a deeply engaging and inspiring woman.

Mountaineering beyond gender

How do you see the relationship between men and women in the mountains?

Our relationship with the mountains is first and foremost an intimate experience. We shouldn't really be talking about men and women, but rather about the masculine and the feminine. Each of us has a feminine and a masculine side to us, and it's these dimensions that we should be talking about. For example, some men may have a very feminine approach to the mountains, while some women may have a very masculine one.

It's interesting to explore what's masculine and what's feminine. If we associate masculinity with risk-taking or commitment, in the virile sense of the word - the desire to show that you're strong, capable of going higher - even if we shouldn't generalize, this may provide an initial clue. On the other hand, if we associate the feminine with greater caution, notably linked to motherhood, or a more aesthetic approach to the mountains, this is another enriching perspective.

In reality, there are as many variations in our relationship with the mountains as there are in our ways of loving. Can we distinguish between masculine and feminine relationships to the mountains? I think so, without falling into caricature or simplification. Men and women don't necessarily love in the same way, and we have to accept these differences. It would be a mistake to write the history of mountaineering by claiming that men and women have the same commitment mechanisms. It's not true: we don't rope up in the same way, we don't go to the head of the rope in the same way. So let's accept this difference and try to turn it into an opportunity for rapprochement and mutual understanding.

Rediscovering the meaning of the mountains: Blaise Agresti invites you on a journey to inner freedom

In your opinion, are attitudes to mountaineering changing?

Unfortunately, I don't think that mentalities are necessarily evolving in the right direction, mainly because of the power of social networks, which impose their standards. What I observe today is that the influence of networks is very strong. People are trying to look like others, to reproduce what they see on the platforms. There's a form of mimetic mountaineering, based on resemblance, which I see as a real tragedy.

For me, the mountains are there to offer everyone a personal inner journey. It could be as simple as taking a walk in the nearby forest, picking up edelweiss, or climbing Mont Blanc. All ways of approaching the mountains are valid.

It's crucial not to erase this diversity, and above all, not to limit ourselves to a strictly sporting approach. Historically, the mountains represented a culture in their own right. Today, it has become almost exclusively a sport, which is rather regrettable. There is a fundamental cultural dimension that needs to be preserved. Some people have mountain wisdom, acquired because they were gamekeepers, poachers, or simply because they know the chamois inside out. The mountain is also a story, a compilation of stories and poetry. The mountains are not just about going fast or climbing summits. It's much more than that. It's a diversity of approaches, practices and sensibilities that we must respect and value.

Blaise, thank you very much for your kind words. What message would you like to pass on to your readers today?

What I'd like to pass on is that we're still lucky enough to have access to this space of freedom. It's often said that the mountains are a place of emancipation, but above all they're an inner journey, a chance to get up there in complete freedom with yourself.

I invite everyone to make the most of the exceptional opportunity offered by free mountaineering, to go where you really want to go. What we experience in the mountains has a special intensity that resonates deeply within us. I sincerely encourage people to look for themselves up there, in the mountains, in the company of loved ones.

With "Une histoire d'alpinisme au féminin", Blaise and Stéphanie Agresti invite us to take a fresh look at how the history of the mountains is told. This sensitive and inclusive approach is in keeping with Blaise's singular career path. To better understand their commitment, I invite you to read our first interview, which retraces Blaise's fascinating career. From mountain rescue to the founding of his management school, Mountain Path, he shares with us his vision of life, driven by humility, openness to others and a constant commitment to passing on his knowledge.