Objective: the Jungfrau

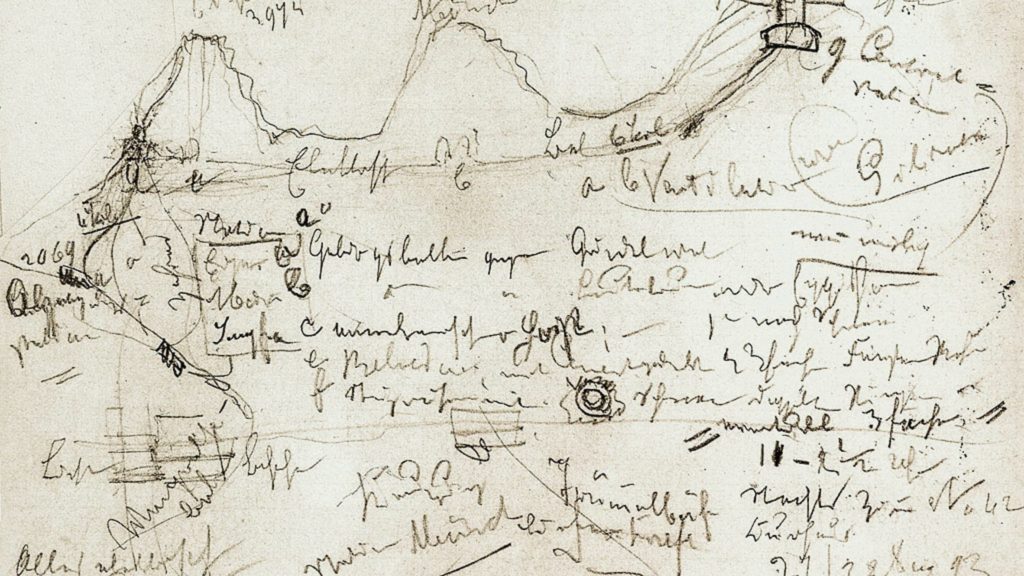

Few people know this, but the objective of the current Jungfraujoch line was not the latter, but nothing less than the summit of the Jungfrau itself. And the partially built line was only the fourth project. Between 1889 and 1890, no less than three projects were developed: by Maurice Köchlin, Alexander Trautweiler and Eduard Locher. While the first two had applied for a concession on 16 and 22 October 1889 respectively, the last one never did. A concession was even granted to Köchlin, but the project was never finalized due to lack of funds. The Zurich entrepreneur

Adolf Guyer-Zeller filed a new application for a concession on December 20, 1893. Unlike his predecessors, Guyer-Zoller did not plan a direct line to summit . Jungfraubut a long route through l'Eiger and the Mönchbefore arriving at the Jungfraujoch and finally at the terminal station, about seventy-seven meters below the summit, which could have been reached by elevator. The advantage of this solution is that it has a much lower gradient.

Oppositions

Even if it was less intense than for the Matterhorn a few years later, the railway of the Jungfrau has also attracted some criticism, more and more numerous as time goes by.

Some, starting from the postulate that the view of summit of a mountain can only be appreciated if one has reached it by one's own means, with effort and even physical suffering, thought that the line was useless and counter-productive. Indeed, a high mountain train can only distort the aesthetic experience and make the view incomprehensible:

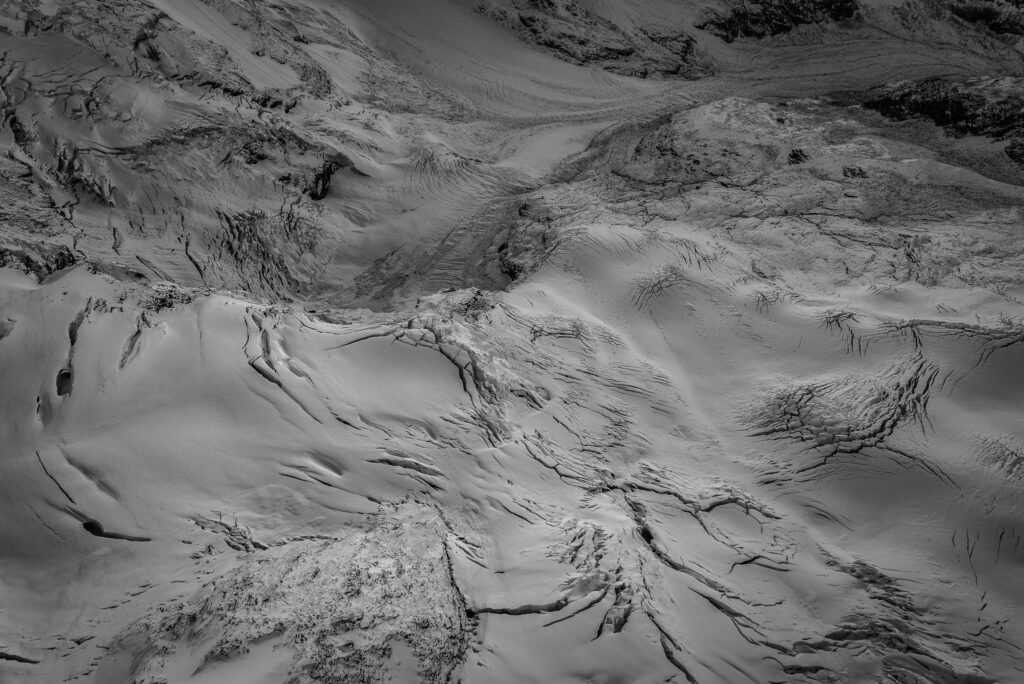

"The sight of the glacier to be understood requires that one has struggled to get there, that one has toiled, frozen, sweated if necessary, and the eye does not really probe the depth of the abysses until the foot has almost slipped into it."

But the opponents were mainly opposed to the line because it was the JungfrauIt was considered by many to be a summit like no other at that time. The Jungfrau was an altar "that must remain pure" and the railroad a profanation, a dishonor making the Jungfrau "a pedestal for the golden calf". Some do not hesitate to make the JungfrauSome do not hesitate to make the railway, with the white cross on the flag, the very symbol of Switzerland.

Many people also did not like the fact that this "masterpiece of nature" was being given away to rich foreigners. The loss of attraction of the mountain for mountaineers was also pointed out.

But also support

But not all opinions are negative. Some are confident, based on the unexpected success of the Rigi and Pilatus lines, that the Jungfrau railroadwill be an excellent venture and that tourists will flock to it, easily replacing the disgruntled mountaineers. The railroad of the Jungfrau will thus be a major attraction relegating the Eiffel Tower to the status of a mere toy.

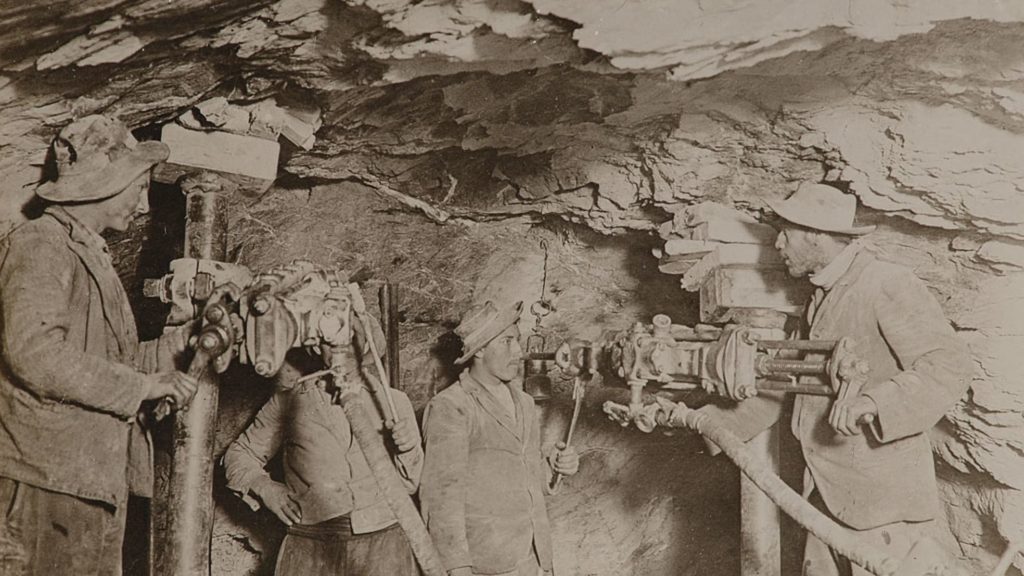

Difficult work and a line inaugurated in sections

Guyer-Zeller financed the bulk of his train with his personal fortune; after his death in 1899, a bank took over the financing with his inheritance. He planned only four years of work, but accidents - thirty men lost their lives, and ninety were injured -, strikes, and difficulties presented by a more capricious geology than expected greatly delayed the work.

The Eigerwand station - offering a beautiful view of the void at Eiger - was only inaugurated in 1903; the Eismeer station (with its impressive glacial expanse) was not reached until 1905; the Jungfraujoch station (3454 m) was inaugurated in 1912, after seven years of additional work.

The construction of the line was thus much more expensive than originally planned: the final cost of the work amounted to sixteen million, more than twice the original budget. The high costs, the First World War and the sharp decline in tourists in the following years meant that the last section was not completed. But even though the line never reached its original goal, the terminal station is still the highest railway station in Europe today.

It was an immediate success: the line attracted nearly 43,000 visitors in its first year.

Related projects

At least two additional projects were added to the initial line: a funicular from the Eismeer station to summit de l'Eiger, but the concession was refused on the grounds that there was no point in having lifts on two neighbouring summits . And a second line, on the Valais side, starting from Brig, was also planned in 1907. It would have consisted of two sections: a cogwheel train from Brig to Zenbächen via Platten and the Belalp hotel and along the Aletsch glacier; then a sled train up the Aletsch glacier via the Märjelensee and Concordiaplatz to the Jungfraujoch station

It should have been ten wooden sleds sliding on the snow and ice, pulled by an endless rope. Flying bridges would have made it possible to cross the widest crevasses. Fearing that it would be too much competition, the railway company of the Jungfrau opposed this line. Although this project never saw the light of day, there was still talk of its realization in 1912.

A scientific observatory at altitude

The concession for the line had been granted on condition that an observatory be built at summit of the Jungfrau. The observatory was eventually built on the Jungfraujoch, but it was not until 1921 that it was discussed again. It was decided the following year to build it on the summit of the Sphinx rock and to install an astronomical observatory there, in order to benefit from the better atmosphere due to the altitude. The astronomers Émile Schär from the Geneva observatory and the Russian Blumbach surveyed the area and came to the conclusion that nowhere had they encountered such favorable atmospheric conditions as at the Jungfraujoch. First measurements even showed that a small optical instrument gave better results than a larger one located on the plain.

Thus, the Jungfraujoch served as an observatory to observe the planet Mars in opposition during the summer of 1924, from July 28 to September 25. In spite of unfavorable weather conditions, the observations from the Jungfraujoch allowed astronomers to have a better knowledge of the surface and atmosphere of Mars and in particular to identify snow on the poles. However, they could not identify the Schiaparelli channels, named after the Italian astronomer who thought he saw straight lines on the red planet, which he characterized as channels - an interpretation that stems from an optical illusion due in part to the average quality images.

Construction began in 1929; the observatory was inaugurated in 1931. Thus, a train that was initially used to bring a large number of travelers to the high mountains also proved to be useful for probing the universe and increasing knowledge in this field, making the mountains no longer a laboratory of nature, but of the cosmos.