A project born in two stages...

The idea came from Dino Lora Totino (1900-1980), an engineer and wool manufacturer from Turin, and Carlo Mollino. Totino was known as the "Count of Cervinia" because he had already built cable cars there in the early 1930s. He had also built the Chamonix the Aiguille cable car. The two men planned a cable car in two parts: the first between Breuil and the Furgggrat and the second between the latter and summit of the Matterhorn. The idea would have appeared in a second time: if we make a cable car to the Furgggrat, why not continue to summit of the Matterhorn ? Totino and Mollino argued that it would be pleasant for the passengers of the cable car to watch, in complete safety from the cabin, the climbers climbing the summit through rocks and snow.

... which attracts criticism

Like the 1907 project, this cable car has been the subject of much publicity and criticism, starting with the autonomous region of Aosta, which did so to protect the natural beauty of the site. As in 1907, one of the main arguments against the cable car was aesthetic: the lifts were rejected because they disfigured the mountain.

Once again, some people did not hesitate to speak of desecration: the Matterhorn, and by extension the high mountains as a whole, was therefore sacred. However, in the 1950s, the link between this sacred mountain and the values of a country is much less present in people's minds, and is only slightly reflected in the oppositions. The Alpine Museum in Bern has organized a thematic exhibition on the Matterhorn to draw attention to what the construction of the planned cable car on the most famous and highest of the Alps summits would mean.

Some even saw this cable car as a threat not only to the Matterhorn, but also to the whole of the Alps, judging that it would be the defeat of Alpine royalty and that the crown would definitively pass to the Himalayas... and that it is there that one should go to seek the emotions procured by an untouched nature

Mountaineers particularly opposed to the project

Even more than in 1907, the mountaineering community opposed the cable car, under the aegis of the International Union of Mountaineering Associations, which did so at the end of September 1950, after meeting in Milan. It even launched a petition. The Italian Alpine Club, resolutely opposed to the cable car, even wanted other countries to interfere in Italy's internal affairs and intervene with the Italian authorities to prevent its construction.

England gets involved

This cable car has also provoked an outcry in England, where many readers have taken up the pen to protest in the press against the project. The daughter of Whymper, the first climber of the Matterhorn, protests and reminds us of the unique character of the Matterhorn. According to her, it would be destroyed by the construction of the cable car. The possibility that the British government would ask the Swiss and Italian governments to do so was even considered. But in the end nothing was done, for the simple reason that it is an internal matter for the countries in question.

In a second phase, perhaps to ward off opposition from mountaineering circles, Lora Totino expanded his project, planning to install a goniometric station at summit of the Matterhorn to guide planes flying over the Alps. This change of heart did not please and it was pointed out that if such a station was really necessary for air safety, it would have already been built... and that in any case it could be built elsewhere than on the Matterhorn.

First stop

The first cost of stopping the project came from Switzerland, when the Federal Council decided - and informed the Italian government - that neither the line nor the summit station should encroach on Swiss territory. It is virtually impossible to build such a ropeway and the corresponding infrastructure at summit without crossing the border.

This decision had a direct impact on the Furgggrat station, complicating its construction to the point of delaying its commissioning by at least a year. The Italian government, basing itself on the legislation in force on the protection of nature, finally refused the concession in the autumn of 1952, before placing it under protection, recognizing it as an international monument, which was precisely the aim of the petition launched by the international committee for the safeguarding of the Matterhorn.

Don't touch the Matterhorn!

Opposition to the funicular railway in the early 1950s was slightly less intense than the opposition to the railroad in 1907. The different social and cultural context, in Switzerland as in Europe, meant that the identification of the nation with the Alps, or even with a particular mountain, was much less present. Thus, the national character of the Matterhorn, the emblem of the nation, is only advanced by a few people. If the aesthetic argument of the denaturing of the Matterhorn is common to both oppositions, it must be noted that it is more adequate in the case of the cable car than the internal funicular. The importance of the Matterhorn as a privileged mountain for mountaineering has increased in four decades and many point to the excessive ease of access provided by lifts as well as the impossibility of enjoying a view if it has not been acquired through effort, even suffering. But in both cases, the main argument remains that you don't touch the Matterhorn... because it is the Matterhorn.

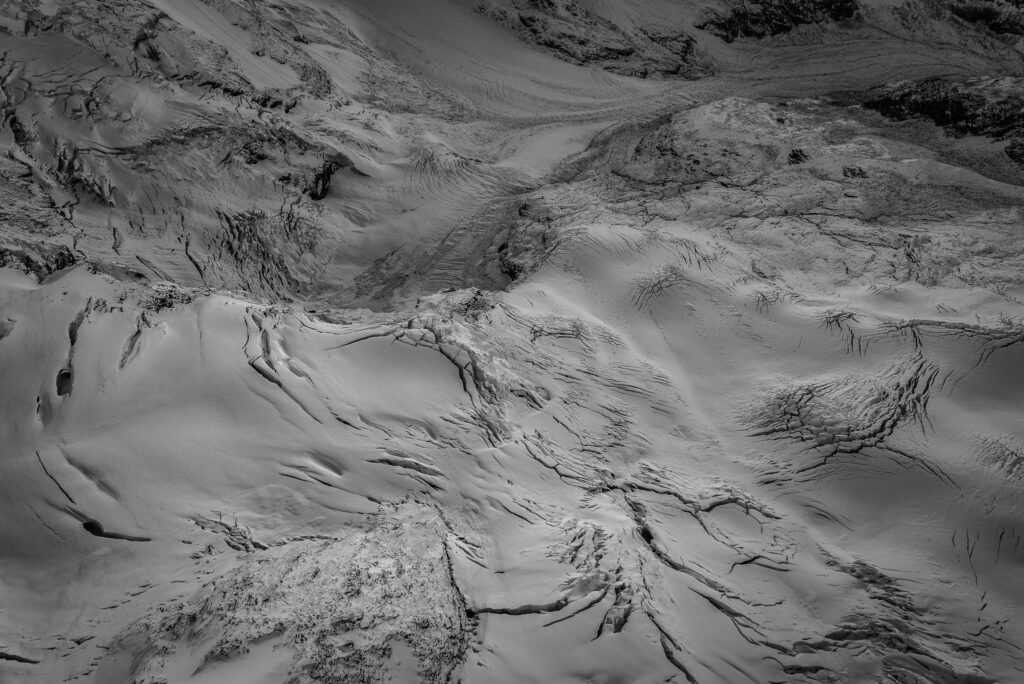

Discover my large format mountain photos in my clients' interiors.

Each print is a limited edition interior design wall decoration.