The means of transportation underwent an important development during the 19th century, as we will have the opportunity to discuss in a future article. Here we will look at an "extreme" project that never saw the light of day, that of a train and a funicular that should have taken passengers... to summit of the Matterhornnothing less!

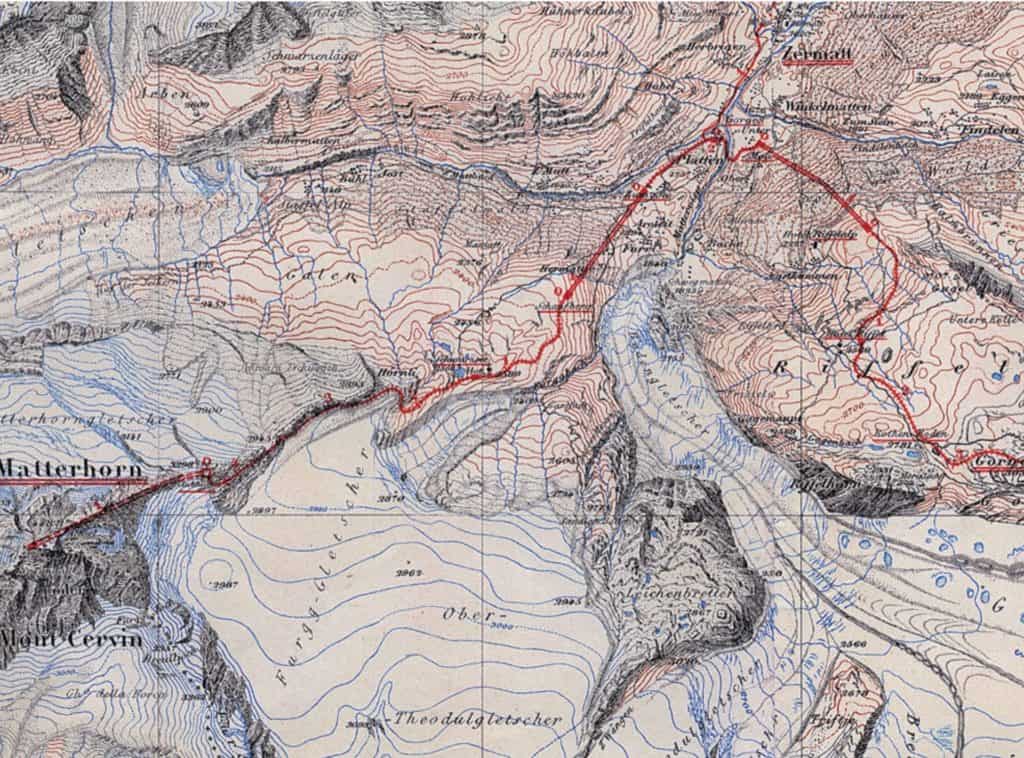

In June 1892, the engineers Leo Heer-Bétrix and Xaver Imfeld obtained the concession for a railway line to the Matterhorn. It was in fact a double concession: one line was to connect Zermatt to the Gornergrat and another Zermatt to the Matterhorn. The first one was built and inaugurated in 1898, which made it the first electric mountain railway with racks. For various reasons that do not interest us here, the second was not built, and the concession expired in 1907.

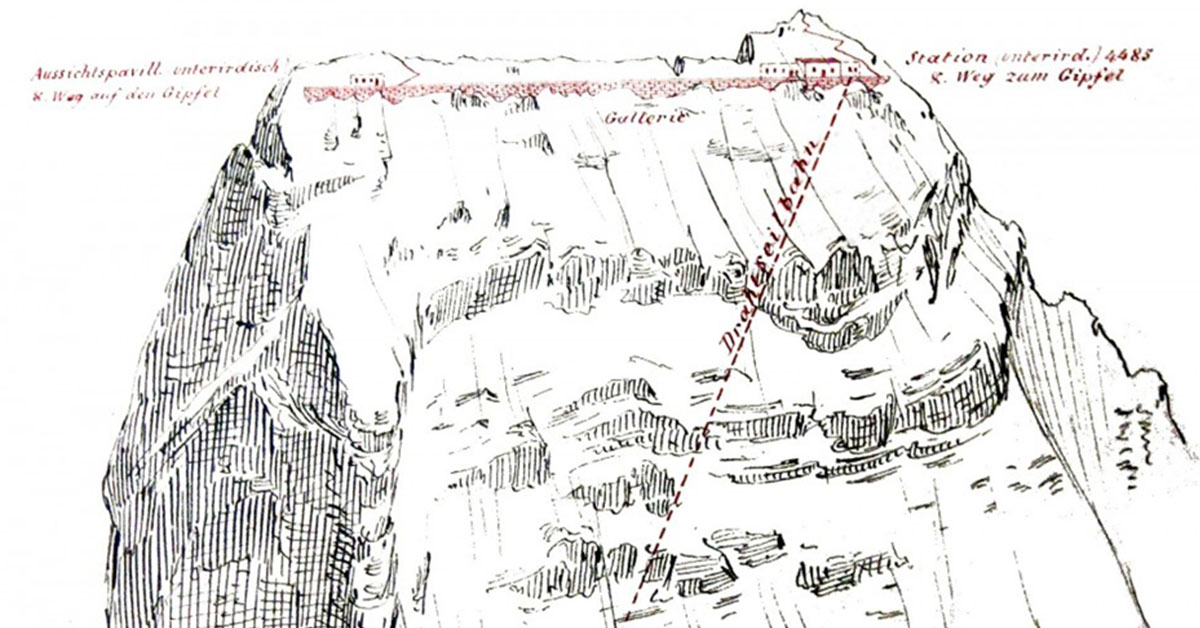

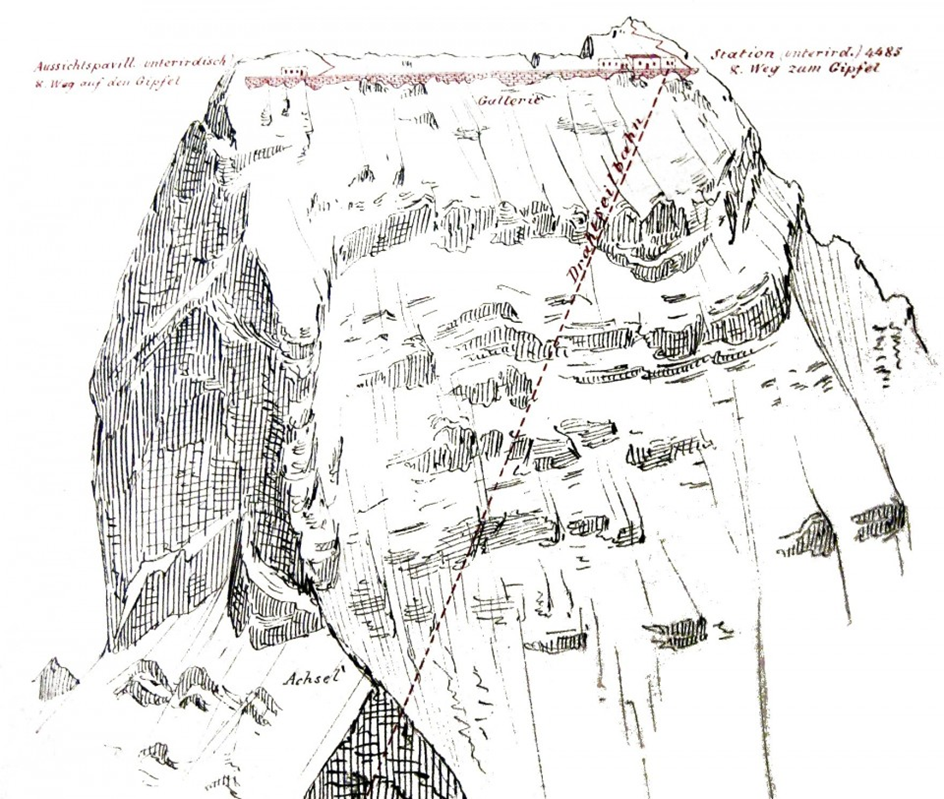

On December 4, 1906, Xaver Imfeld and Henri Golliez, another engineer, submitted a new application for a concession for a line connecting Zermatt to summit . To climb the Matterhorn, a two-part route was planned: the first is a rack railway to the Hörnli ridge at 3052m via the Schwarzsee (2850m), the path between the latter and the Hörnli being in an underground gallery; the second is a funicular railway leading to the final station, only 20 meters below the Matterhorn summit .

The slope for the second part of the route was between 85 and 95%. Golliez and Imfeld had planned a restaurant and a panoramic gallery at the finish station, but also a pressurized room to counter the effects of altitude on people suffering from altitude sickness. A path would also have been built to reach summit of the Matterhorn.

The line should have been in operation from July to the end of September. With the recent opening of the Simplon tunnel (1906 ) and with the construction of the future Lötschberg tunnel on the line between Bern and Brig, the two engineers thought they could attract thousands of travelers. The influx of tourists had doubled after 1891, following the opening of the railroad linking Visp to Zermatt.

The total estimate was 10 million francs, 3.6 million for the train to Schwarzsee, 3 million for the funicular to summit of the Matterhorn, and the rest for rolling stock, administration costs, etc. The rest was for rolling stock, administration costs, etc. This was a very large sum at the time. The engineers predicted that the work would take four years. The price of the ticket to reach summit was 50 francs, a large sum for the time, but it should be compared to the 180 francs needed to climb the Matterhorn: 100 francs for the guide and 80 for the porter. The total journey would have taken one hour and twenty minutes and openings in the wall would have allowed the travellers to admire the landscape during the ascent.

Of course, this train never saw the light of day. Although the line Zermatt-Gornergrat was inaugurated with great pomp and circumstance in 1898, mentalities changed and this project caused a real outcry in Switzerland. The Heimatschutz and the Swiss Alpine Club in particular went to the front and launched two petitions to ban the train. More than 70,000 people signed the petitions. The debate in the press of the time was also fierce, and we will give a brief overview here. Imfeld and Golliez themselves took part in it.

One of the main arguments put forward by the opponents of the train is the defense of the landscape and the sacredness of the high mountain areas, and this has been the case since the beginning of the debate. For Charles-Marius Gos, for example, "under the pretext of progress, we are cowardly allowing real sacrileges to be carried out". The columns of the Gazette de Lausanne of Tuesday, June 11, 1907, spoke bluntly of "the desecration of the Matterhorn".

The opponents also put forward patriotic, even nationalistic arguments. Gonzague de Reynold even made this the only argument: "Should the Swiss people allow one of the most beautiful treasures they possess to be commercialized for the benefit of two or three engineers, a dozen shareholders and a few hundred foreigners? In fact, for Reynold, granting the concession to the two engineers would even amount to selling patriotism back to foreigners. He also reminds us "that a people is close to its decadence, when it loses the notion of its moral existence, whose symbols it no longer respects". It is thus necessary to sign the petition, "not to let create a Previous on which would depend the ruin of our Alps, and, by counter blow, the ruin of our moral independence".

The journalist Auguste Schorderet goes in the same direction in his play Le Cervin se défend! The message of the play is that the influx of (wealthy) foreign tourists would disturb the "simple and authentic" customs of the Swiss, who would thus lose their identity, but also that Swiss symbols should not be touched. The Matterhorn was already a symbol of Switzerland at the time. And it was precisely this Matterhorn symbol that justified this patriotism.

Henri Golliez himself took up the pen in the Gazette de Lausanne to defend the project, and above all to answerErnest Bovet's attacks, to which he replied point by point. The engineer defended himself from being unpatriotic, answering that any engineer who had made or wanted to make a mountain railroad should be given the same epithet. Golliez does not understand the distinction made by Bovet in the different mountain railways: "Is a railroad honourable on one peak, ignominious on another? Is it honorable at 3000 meters and infamous at 4000?

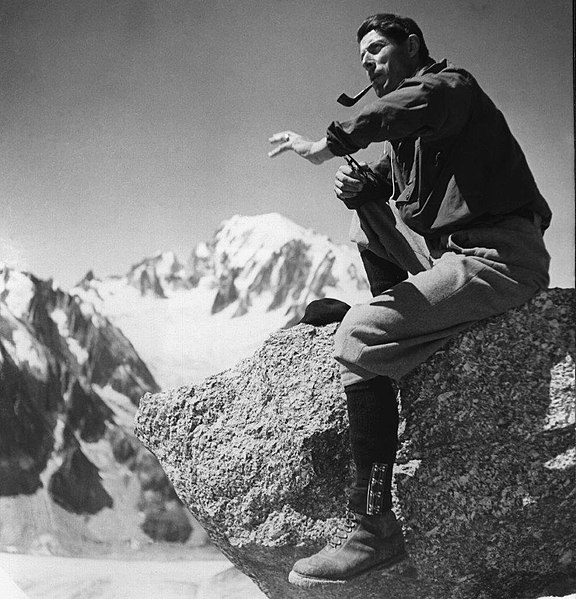

In this whole affair, Gos even asked the opinion of Edward Whymper, the first climber of the famous mountain, as the writer himself will tell it in his book Près des névés et des glaciers : Indeed, the mountaineer, 67 years old now, refuses to take a public position stating that this affair concerns the Swiss and that if he took a position by writing in Swiss or English newspapers, he could be told to meddle in his affairs. Whymper begins his letter, however, by stating that he does not like the project. However, Whymper seems to change his mind as he writes his letter because he concludes it, after signing it: "You are at liberty to publish this anywhere".

"I had written to him, begging him, rather begging him, the hero, to protest openly against the project. His revered voice would not have failed to rally all the skeptics and the indifferent on the right side. He did not do so.

Under the pressure of popular opinion, the Federal Council never granted the concession to the two engineers whose deaths, in 1909 for Imfeld and in 1913 for Golliez, sounded the final death knell for this train. The Matterhorn affair reveals that the galloping technologization of the Alps should not be carried out at any price, or in any place. The affair also shows the emergence of the idea that the high mountains are a sacred space - it would seem that things have changed since then...