I crossed paths with a mountaineer driven by a desire to serve and help people. Blaise Agresti, former head of the Peloton de Gendarmerie de Haute Montagne (PGHM) in Chamonix, mountain guide, founder of Mountain Path and passionate author. A career shaped by summits, mountain rescue and the art of management. His life is both daring and thoughtful, focused on sharing and humility. I had the privilege of listening to his words, experiences and convictions. An inspiring dialogue that I'm delighted to share with you.

Blaise Agresti: the art of guiding to the summit

You have had a rich and varied career. Former commander of the PGHM, mountain guide, founder of Mountain Path, author of numerous books and lecturer. Can you tell us more about your background?

Deep down, I've always wanted to be of service, with a "boy scout" dimension very much present during my childhood. When you combine this mountain background with a deep-seated desire to help others, the path to mountain rescue comes quite naturally. Becoming a guide, and then joining the mountain rescue service, was the first major step in my professional life.

Mountain rescue was the ultimate goal. As an officer, I held every possible position: head of the PGHM in Chamonix, head of the CNISAG (Centre National d'Instruction de Ski et d'Alpinisme de la Gendarmerie), and director of all the PGHMs. I then moved on to officer management in the Gendarmerie, with a stint in Paris to attend the war school and join a staff. I was then placed in charge of a department as a colonel. At that point, I was offered a job in the private sector with the Petzl company in Grenoble, but the position didn't really suit me.

That's when I asked myself: "What if I started my own project? And so Mountain Path was born, an initiative in perfect continuity with everything I'd been doing since childhood: enjoying the mountains and using them as an educational tool.

Blaise Agresti and the mountains: between caution, wonder and lightness

What is your relationship with the mountains? How does mountaineering make you feel?

Mountains are dangerous. That's something you should never forget. You must always keep your feet on the ground and remain very humble in your approach to the mountains, both physically and in terms of the risks involved. Humility and vigilance are absolutely essential.

Beyond that, I remain extremely sensitive to two essential aspects. Firstly, beauty. I still take photos when I climb Mont Blanc with clients, especially at sunrise. I've kept intact my delight in the aesthetics of a sunrise or sunset, the elegant shape of a ridge, or the arabesques of snow created by the wind. I find all this absolutely fantastic, because we have the privilege of evolving in the midst of real paintings. Some days, you feel as if you're walking through a masterpiece, as if you're walking inside a Van Gogh painting from morning to night. Of course, when it's foggy, this feeling may be less intense, but most of the time, you're literally walking through a living painting.

The second aspect that's close to my heart is the fun factor. When you ski in powder snow, you immediately rediscover your childlike soul. Even today, when I ski in powder snow, I feel a deep sense of happiness: you jump around, you laugh, you're just happy. It's a kind of lightness.

Finally, what I deeply appreciate is the subtle cohabitation of beauty, caution in the face of danger and joyful lightness. To be able to experience so many sensations and emotions in a single day is quite something.

Mountain Path: the Chamonix high-altitude management school

You are the founder of Mountain Path, the altitude management school. Through experiential learning paths, you address a wide range of themes, including leadership, crisis management, team cohesion and the major challenges of tomorrow. Can you tell us more about your business and the teaching approach you offer?

Mountain Path is a project that follows in the footsteps of my entire career. I've been lucky enough to be immersed in the mountain world since I was a child. So I've inherited a very strong alpine culture. This heritage rests on three pillars. The first is the natural world itself, the beauty of the mountains. In a world in difficulty, it's crucial to maintain this relationship with beauty. That's why I think it's essential to invite people to marvel at the beauty of the mountains, while at the same time making them aware of the worrying speed of their degradation, particularly that of the glaciers. So there's a double dimension to mountains: wonder and warning.

The second pillar is the guiding profession. A guide takes his companions into the mountains and exercises strong individual leadership. He must constantly adapt, which can really inspire and help many people to evolve in a complex world. This adaptability and individual leadership are at the heart of our programs.

The third pillar is mountain rescue. Here, we enter the world of the collective, of the team, where several professions cooperate closely: the aeronautical profession with pilots and mechanics, the medical profession with doctors and hospitals, and finally the mountain rescue profession itself.

We use these three pillars to build programs for a wide variety of companies, ranging from the executive committees of major groups to start-ups and family businesses. Over the course of a year, we support dozens of companies through conferences, workshops and mountain seminars.

Our initial conviction is that current educational models are very much focused on the transmission of knowledge. For our part, we favor an experiential pedagogy: first, people live an experience intensely; then, they debrief and analyze it individually and collectively. It is only after this process that they become receptive to theoretical or practical inputs, enabling them to truly transform themselves.

More about Mountain PathHow do you think mountain experiences can help managers to better manage uncertainty, pressure and decision-making in the workplace?

It's the deconstruction of oneself and one's way of perceiving things, followed by a personal reconstruction. I can draw a parallel with Plato. Plato makes much use of the metaphor of the cave, where the world is but a representation of shadows cast on the wall of this cave. We use the mountain as a metaphor similar to that of the cave, but not with the aim of turning managers into mountain people. We use it to reveal those shadows cast by the self. When we place someone on a rope with his or her colleagues on a management team, in a situation that requires cooperation, adjusting the length of the rope or trusting each other, many things become immediately visible. It really is a pedagogy based on metaphor.

To return to Plato, his fundamental conclusion is the birth of ideas. If individuals are placed in conditions conducive to experience, understanding and questioning, then ideas emerge naturally. Being immersed in an unfamiliar environment, such as a mountain, and learning to walk in it, is extremely conducive to the birth of obvious, powerful and often surprising ideas. These ideas then emerge on their own, in a quite remarkable way.

"Une histoire d'alpinisme au féminin": making the invisible visible

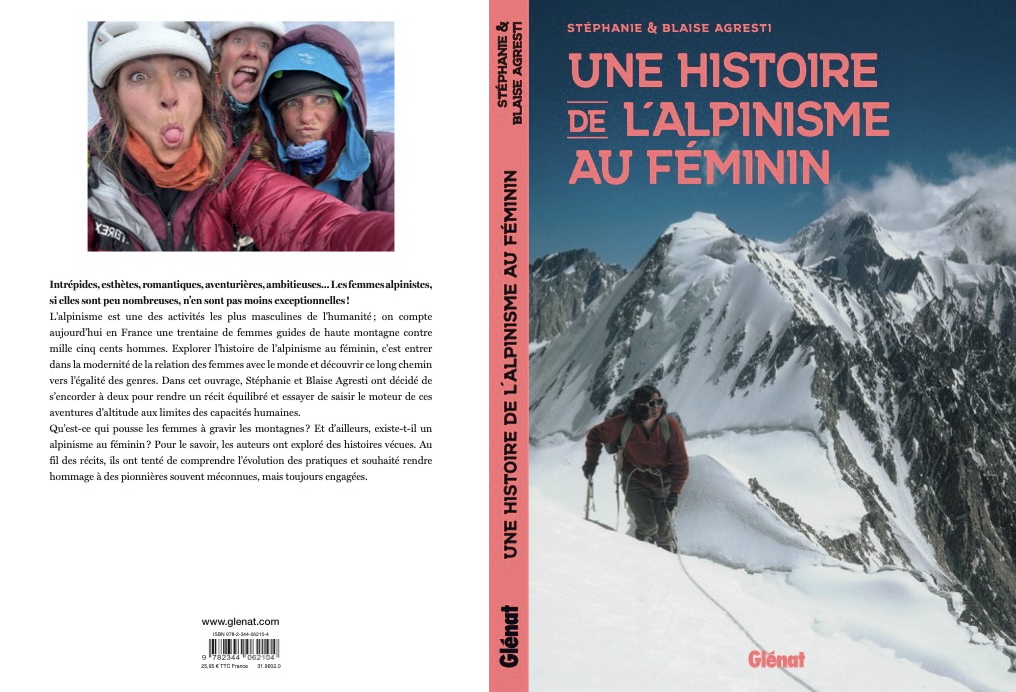

Let's talk about the release of your new book "Une histoire d'alpinisme au féminin", co-written with your wife, Stéphanie Agresti. How did you come to write this book?

My mother is on the cover of this book. She was a mountaineer with my father and took part in many expeditions. As it happens, over fifty years ago, in 1966, she climbed a summit of over 7,400 meters in Afghanistan. At the time, she was described as "the highest woman in the world", although in reality she was perhaps the second or third to reach that altitude. In any case, she was one of the women who reached the highest altitudes at the time. No one, however, really cared at the time.

Throughout my childhood, we regularly welcomed mountaineers, men and women from all over the world. For example, Wanda Rutkiewicz, one of Poland's greatest mountaineers, came to stay with us. There was also Sonia Livanos, to whom my parents were very close, Catherine Destivelle, and Martine Rolland, the first female guide.

Thanks to my mother, I came into close contact with these women mountaineers. Today, I feel a profound discrepancy between my childhood and teenage experience, when the mountains were naturally open and balanced, allowing women their full place, and the official narrative, which has almost totally erased them. From Marie Paradis in 1808 to the present day, many women have achieved extraordinary feats. True, their physical performances may have been slightly inferior to those of men, but they were nonetheless remarkable, especially given the social contexts of their times.

It was this idea that drove Stéphanie and me to write this book. We did extensive research, discovered some incredible profiles, and wrote this book, of which we're very proud. This book is a modest attempt to make up for some historical oversights, even if, as I often say, it's only an introduction to the subject.

At Editions Glénat, there are two separate books: "Une histoire de l'alpinisme" and our book devoted specifically to women's mountaineering. The day these two books become one, the problem will finally be solved. The very fact that there are two separate books, one regarded as the official history of mountaineering without women, and the other devoted entirely to women, still says a lot about our society. As long as these stories are not naturally integrated into a single grand history, we still have a great deal of educational work to do. And we know that this work is far from over.

Blaise Agresti continues to inspire us, driven by his desire to pass on and enlighten our view of mountaineering. I invite you to discover the continuation of our discussion dedicated to the release of his new book, "Une histoire d'alpinisme au féminin", co-written with his wife, Stéphanie Agresti. A captivating discussion that breaks some of the current codes of mountaineering and invites us to reflect on our own approach to the mountains.