In 2025, Léo Billon once again confirms his qualities as a top-level mountaineer. This summer, with Enzo Oddo, he signed the first free ascent of the Lafaille route at Les Drus, considered to be the hardest route in the Mont Blanc massif. A member of the Groupe Militaire de Haute Montagne (GMHM), Caporal-Chef looks back on his career, his encounters and his landmark expeditions. He also shares his thoughts on the mountain environment, his relationship with danger and the qualities required to reach the highest level. Interview with Léo Billon, one of the finest mountaineers of the 21st century.

Léo Billon: the roots of a passion

Hello, Leo. Thank you for accepting my invitation! Can you tell us how the mountains came into your life?

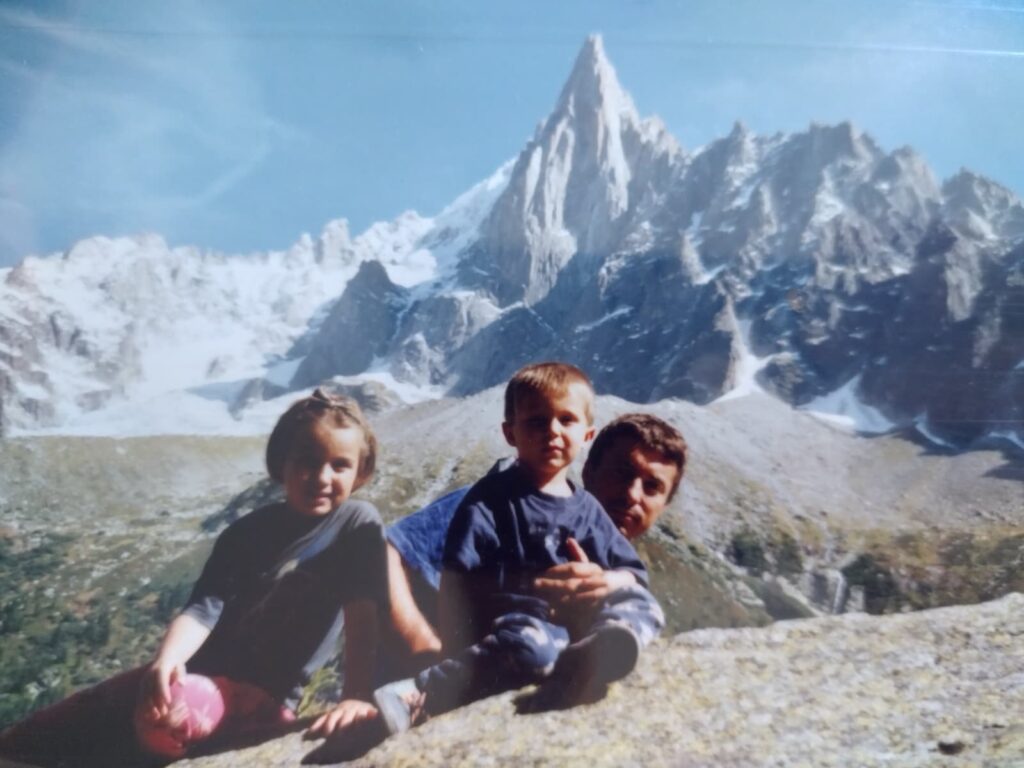

I grew up in the heart of the Drôme, in a family deeply attached to the mountains. With my sister, we were surrounded by this universe: hiking, climbing... Our parents passed on this passion to us very early on. My environment and my sister naturally led me to a high school focused on sports and outdoor activities. We practiced climbing, caving, canyoning, kayaking, ski touring... a wide range of activities that further strengthened my bond with the mountains. At the same time, we spent almost all our family vacations in the mountains. My father, a mountain guide, would take us climbing and exploring different massifs.

Did you always want to make mountaineering your profession?

Until I started studying to become a mountain guide, I never thought I'd become a professional mountaineer. It was only when I met Max Bonniot and Sébastien Ratel that the idea began to take root. It wasn't a clearly formulated objective, but rather something that was obvious to me through my climbing: I was making progress, I was committing myself more and more, and naturally, I was heading for the top level. Then, little by little, circumstances and encounters opened up this path for me. The GMHM, for example, was a real opportunity. If I hadn't met the right people, I probably wouldn't have had this career path.

Léo Billon: his life as a top-level athlete with the GMHM

In concrete terms, what does the GMHM expect of you? Do you have a typical day?

There's no particular requirement at the GMHM, other than... to climb mountains. The most important thing is to make personal and collective progress. Everyone arrives with their own level, and there are obviously differences between members.

What counts above all is the dynamic, the intention: to be invested, motivated, seeking to progress, and perhaps aiming for high-level mountaineering. In a context where practice involves risks, it would be difficult to impose anything on GMHM members.

In reality, we expect everyone to bring their own projects to the table, in all the diversity and richness of mountaineering.

Léo, in 2023, you enjoyed a magnificent adventure in Patagonia with members of the GMHM, crossing the Campos de Hielo. Can you tell us more about this expedition?

We embarked on a rather atypical expedition, one that went beyond the GMHM's usual frame : crossing the Patagonian ice caps from north to south. These two immense ice caps stretch for almost 600 kilometers, separated by fjords. We covered them in their entirety, in total autonomy, for forty-five days.

To link the two ice caps, we took kayaks on board to transport our equipment and food. It was a radically different experience from our usual ones. We usually spend four to six days on a large vertical face. Here, we had to walk, day after day, on the horizontal, with everything we needed to survive: food, equipment, complete autonomy. No supplies, no outside contact.

During these forty-five days, we only came across two old shepherds, at the exit of the first cap. They lived in abject poverty. It was a memorable, unlikely encounter.

Awareness and lucidity: the keys to top-level mountaineering

If you had to pass on one lesson to a mountaineer aiming for the top level, what would it be?

For me, the most important thing is to do things consciously. Being aware of your desires, your motivations, what drives you to practice... and then staying present in every gesture, in every moment. This, I believe, is the basis of a healthy relationship with the mountains.

In practical terms, this means asking ourselves: what makes me want to go mountaineering? What motivates me? Is it intrinsic or extrinsic motivation?

There's no right or wrong reason. Even the way others look at you can be a driving force. The important thing is to be aware of it. Because this lucidity enables us to be aware of our own biases when it comes to making decisions. It allows us to move forward in our practice with balance and clarity.

What's your relationship with danger in the mountains?

I've always been a very timid person. It's paradoxical, because you wouldn't think so, but it's true. And in a way, I think that's what drew me to the mountains. I also went there to learn how to manage my emotions and tame my fears. Not just in mountaineering, but in life in general.

At first, I was afraid of everything. I was worried, stressed and anxious. Then, with time, experience and knowledge of the environment, I learned to relax, to read my surroundings with a little more clarity and objectivity. What I discovered was that my fear was not a handicap, but an ally. It kept me focused, attentive and lucid. It's always been a good advisor, a driving force even when there's danger in the mountains. And above all, it never degenerated into panic. For me, fear has always been a guide, a stimulant, never a brake. It has allowed me to question my choices and those of my companions, to try and understand myself and others.

Perception vs. reality: why are mountains so hard to read from the outside?

Mountain guide, rescue worker, GMHM member... These professions all seem to belong to the same mountain "elite". For a non-alpinist, it's hard to grasp their real differences. Can you tell us what makes a rescue worker, a member of the GMHM and a mountain guide so different?

The GMHM can be seen as a kind of "national mountaineering team". On the other hand, being a mountain guide or a rescue worker with the Peloton de Gendarmerie de Haute Montagne (PGHM) has little to do with high-level mountaineering. For the general public, these figures embody mountain experts - and this is true, but in a different register. A mountain guide, for example, holds a "brevet d'État" (state certificate) that allows him or her to supervise. At the end of his training, he has a solid understanding of the environment, but that's just the basics. To compare, it's a bit like a "departmental" level compared to the "international" level represented by high-level mountaineering.

It's not the role of the PGHM or a mountain guide to practice performance mountaineering: the former are first-aiders, the latter are supervisors and trainers.

The problem is that the mountain remains difficult to read from the outside. There are so many disciplines, so many styles, and no strict competition or frame reference to rank performance. For many, hearing a mountaineer say he's climbed the north face of the Grandes Jorasses is an achievement. But in reality, this face offers a wide range of itineraries with very different levels of difficulty, from relatively accessible to high-level.

This spring, you climbed the three most legendary north faces of the Alps - the Eiger, Matterhorn and Grandes Jorasses- with Benjamin Védrines, in just six days. This feat has received a great deal of media coverage, yet you don't consider the expedition to be an exploit. Can you tell us more about it?

My objective was simply to accompany Benjamin Védrines, who wanted to climb the three north faces of the Alps by the most classic routes, linking them by bike. Basically, this wasn't my project. My year was mainly devoted to climbing, with specific training that wasn't very endurance-oriented. Benjamin was simply looking for someone to accompany him. I accepted one race, then a second... and finally all three. Between each face, when he was pedaling, I took the opportunity to continue my climbing training.

For Benjamin, it was above all a scouting trip with a view to a more ambitious future project. For me, it was an opportunity to share an adventure with a friend, with no particular objective. However, from the outside, the sequence can impress and arouse admiration. Without explanation, it's easy to see it as an extraordinary feat. In reality, for me, it was just a "sub-project", and for Benjamin Védrines, a preparatory stage. The difference between the perception of outsiders and our actual experience is often striking.

When you're asked "Which of all your projects do you consider to be the most difficult or the most challenging?", you don't really know what to answer. And why is that?

I can compare mountaineering to athletics: it's a mosaic of incomparable disciplines. How can you compare a marathon runner with a javelin thrower? This summer, I made the first free ascent (with shoes on) of a route in Les Drus with Enzo Oddo, which was an outstanding experience. But how can I compare it with the trilogy I completed with Benjamin Védrines, which included a series of mixed routes on Les Drus, Les Droites and Les Grandes Jorasses in three days, all free climbing? Both projects are essential to my career, but impossible to prioritize. Just as it would be pointless to compare a marathon time with a javelin throw. Each style has its own value.

Léo, thank you for this interview. In the end, between all these achievements and your quest to always be at the top level, are you still looking for "pure pleasure" with no performance stakes?

Today, I find more and more pleasure in performance, but I still enjoy simpler, less ambitious races.

My motivations have changed a lot since I started out. In the beginning, I was almost bulimic: I would multiply my outings, without necessarily looking for difficulty, just to be in the mountains. Over time, my volume of practice has decreased, but it has become more refined. I now focus on precise objectives, which I anticipate and prepare for in a targeted way. Little by little, I've become more professional, directing my training towards concrete projects.

For example, this year I devoted most of my preparation to climbing, as we had planned an ascent of Les Drus. I knew that the key would lie in this discipline. Last year, on the other hand, my main objective was the Janu in Nepal. Back then, I focused all my preparation on endurance, because that was the decisive factor for this summit.

Léo Billon continues to make us dream. Driven by his quest for performance, he never stops pushing back his own limits. He loves exploits and challenges. But he continues to approach them with wisdom. Because in the end, perhaps that's what high-level mountaineering is all about: reconciling ambition and lucidity in the face of the mountain's grandeur.

Similar Articles :