High mountains have always held a special place in people's hearts. An object of fear or fascination, a devil's lair or a divine creature. The Alpine 4000s forge ideals just as they arouse fervor. But beyond the mere desire to conquer them, man sees in their immensity the means to experience high altitude. To experiment at the gates of the sky, to advance his knowledge. From the 18th century onwards, high summits became observatories. The time had come for the first scientific research in the Alps.

Scientists take their first steps at the summit the Alps

The Age of Enlightenment marked the advent of the scholar-traveler. These pioneering scientists left their books to venture to the four corners of the globe. Horace-Bénédict de Saussure was one of the first to study the effects of altitude on the summit Mont Blanc. In 1787, he went there with Jacques Balmat to measure its elevation, which he then established at 4,775 m. Fascinated by Alpine flora, he conducted research in the heart of the Alps and the Mont Blanc massif in fields as varied as botany, geology, meteorology, glaciology, physiology and atmospheric physics. His work has paved the way for a new era in which wild nature plays the leading role.

At the same time, Déodat Gratet de Dolomieu took a mineralogical approach to the mountains. What are these gigantic pyramids made of? To gain a better understanding of their composition, in the summer of 1789 he trekked across the Alps to the Monti Pallidi. He became the first scientist to analyze this unique rock, named dolomite in his honor.

A few years later, in 1831, James David Forbes measured the seasonal movement of glaciers for the first time. Observing the Mer de Glace, he defined the "Forbes Bands". This succession of light and dark waves can be seen on the surface of glaciers, allowing us to measure their progress through the seasons.

In 1860, Louis Pasteur chose Mont Blanc as his experimental site. He conducted research on air quality at altitude. Visionary explorers, these scientists were able to push back the boundaries of science in order to advance it. The foundations of alpine search were laid.

The first observatories at the summit the Alps

On Mont Blanc, the Vallot and Janssen observatories

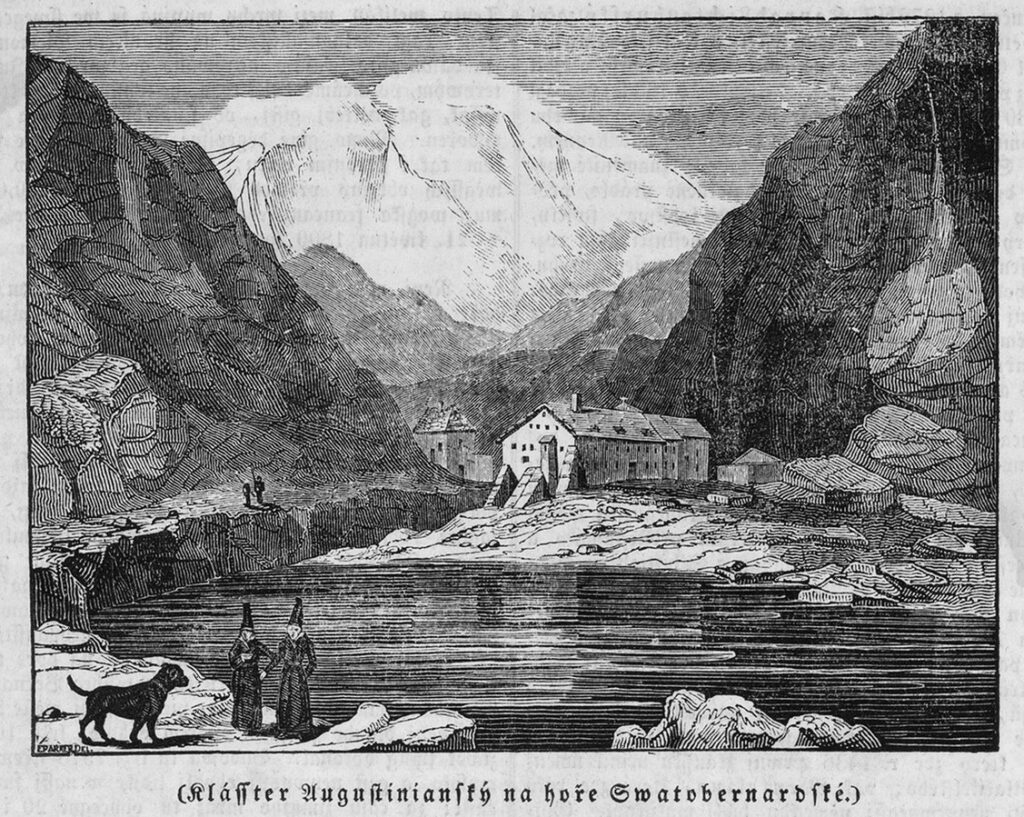

In 1893, Jules Janssen set up a temporary observatory on the summit Mont Blanc to observe the solar spectrum in the best possible conditions. Laid on the ice without any foundations, the structure was dismantled in 1909.

By this time, Mont Blanc already had its own observatory. As early as 1890, Joseph Vallot had built his first laboratory at an altitude of 4,365 m. At the time, little was known about life at altitude and man's ability to adapt to it. Many doctors, for example, felt that sleeping in the mountains at such a high altitude could be dangerous, if not fatal. Joseph Vallot set out to unravel the mysteries of this world perched between earth and sky. The observatory was enlarged in the following years, then rebuilt in 1898 on the site it occupies today. Located at 4350 m, the Vallot Observatory became a multidisciplinary search center where scientists studied meteorology, glaciology, cartography and physiology, among other subjects.

On the Jungfraujoch, the Sphinx observatory

The Swiss Alps are no exception when it comes to exploring the peaks. Built under the impetus of Walter Rudolf Hess, the Jungfraujoch scientific station was inaugurated in 1931. The Sphinx Observatory, one of the highest in the world at 3571 m, was equipped with its first astronomical dome in 1950. This leading search center houses laboratories for astronomy, meteorology, glaciology and physiology. It has been the scene of major scientific breakthroughs. Thanks to the atmospheric and environmental studies carried out here, it has become a benchmark in the field of climatology.

Early scientific research in the Alps : Life at altitude

The high mountains provide an ideal frame for scientists to carry out their astronomical and meteorological observations. The atmosphere is clearer and the sky clearer than in the valleys. The work carried out at the Sphinx observatory has enabled us to gain a better understanding of the properties of the atmosphere and cosmic rays, and to gain a new perspective on climate change. At the Vallot observatory, observations of solar radiation have been all the more precise and innovative in view of the scarcity of atmosphere at the summit Mont Blanc.

In addition to its contribution to astronomy and climate, the high mountains provide scientists with the means to improve their geophysical knowledge. What is a glacier, its structure and evolution over time: aren't the Alps the best place to answer these questions? Following in the footsteps of 19th-century researchers, Robert Vivian and his team spent a week isolated beneath the Argentière glacier, studying its movements. Such initiatives laid the foundations for glaciology as an alpine science.

The human body's reaction to altitude also became a subject of study. As early as the 18th century, Horace-Bénédict de Saussure noted that high altitude caused him extreme fatigue. In the early 20th century, physiologist Nathan Zuntz was one of the first to study the effects of mountains on human beings. He concentrated on the question of fatigue, while at the same time, physician Angelo Mosso focused his research on the consequences of altitude on the human body. The stakes were high: if man was to tame this hostile universe, he had to understand its exact impact on his own body. Dyspnea, vertigo, cerebral congestion, hypoxia and acute mountain sickness. All of these ailments make life difficult for him when he climbs to heights of over 3,000 m. It's through experience and questioning that science progresses day by day.

Early scientific research in the Alps built a bridge between man and the elements. As the precious foundation of our knowledge, they paved the way for modern science. Today, more than ever, the high mountains are at the heart of our concerns. Studies carried out in observatories, on glaciers or on mountainsides enrich our knowledge and shed light on debates on climate and the environment. At a time when reality is sometimes shrouded in vain illusions, the Alps offer science an invaluable source of insight.